by Alex P.

I’ve always been drawn to crime films, from Fritz Lang’s “M” to classic film noir to Martin Scorsese’s extensive gangster film output, with their allure of hidden underworlds of organized crime and the handsome rewards it brings at the risk of it all falling apart at any moment. Whether you identify with the criminal masterminds or with the police detectives hot on their trails, it’s a strain of cinema that’s had appeal since the inception of film itself and 1903’s The Great Train Robbery.

One sub-genre of crime that’s stuck with me is the heist film. There’s something exquisitely thrilling about watching a heist carried out from the planning stage to the execution where it all goes so right or so wrong; think Baby Driver and The Bad Guys for popular recent examples.

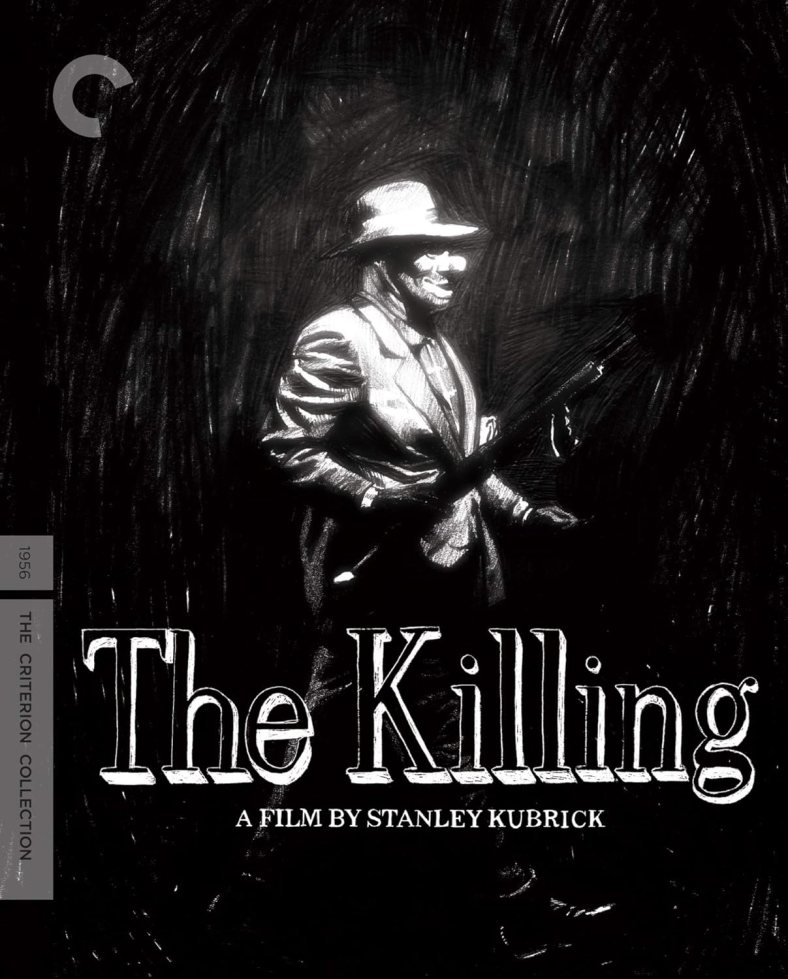

Director Stanley Kubrick’s shadow still looms large over the art of film, but some people may not know one of his earlier films, The Killing, a 1956 heist noir that gave Kubrick his first critical success. Many know the 1968 ensemble comedy Dr. Strangelove, his last black and white film before the monolithic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Fewer know of Lolita (yes, that Lolita), Spartacus, or Paths of Glory, but I suspect the most obscure are his first three films. Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss are independent, exploratory films where Kubrick was finding his footing; these were followed by The Killing, starring the elusive Sterling Hayden, which was a real home run.

The Asphalt Jungle was a foundational heist films, and it seems clear that Kubrick wanted to emulate it a few years later with The Killing. Kubrick plucks Sterling Hayden from The Asphalt Jungle’s all-star cast to play Johnny Clay, the mastermind behind a heist at a horse-racing track. Clay remains a mysterious and dominating figure, and much of the story is dedicated to the setup of the heist and the ensemble of his hired co-conspirators. More of the tension comes from a psycho-sexual rift between George, the racetrack cashier, and his wife Sherry, who overhears the plot and schemes to take George’s money and run. This sub-plot strikes me as The Killing’s weakest aspect, as it is far too maudlin and the sets are cheap, complete with a fake parrot. The rest of the cast, though, comprise a thrilling ensemble of characters, each of whom plays a perfectly compartmentalized part.

Johnny Clay, as played by Hayden, is a complete enigma. Just out of prison, he immediately starts moving on the heist. He conducts himself with an affect so cool and calculating that it strikes the viewer as sociopathic. My favorite participant in his heist is Maurice, played by Georgian wrestler Kola Kwariani. He’s a highly intelligent, thoughtful, soft-spoken man who works in a chess club, and it is tragic to watch Clay pay him to get drunk and start a fight, reducing a smart and sensitive man to hired muscle. Every participant is meticulously positioned to play a separate part in his scheme while remaining unable to implicate him if they fail. It’s so well-planned, and the execution is mesmerizing and unforgettable, but so are the inevitable snags along the way.

When comparing The Killing to The Asphalt Jungle, I’ve found that the inherent moral ambiguity makes Kubrick’s heist film memorable, as the start of a theme that continued throughout his career. In The Asphalt Jungle, the charming and likeable criminals are served their just desserts, complete with a speech by the police to an eager press pool that feels straight out of a public service announcement. While in The Killing, the brief but poetic comeuppance that comes to the Clay at the film’s end comes instead from a cruel and simple twist of fate. Instead of seeking answers from the morals and standards and the laws of his era, Kubrick looked to bad luck and the randomness of the universe.

Like many overlooked greats, The Killing can be found on Kanopy using your library card. Though I mostly use it for hidden gems that can’t seem to find their home in more commercial environments (take, for example, The Hudsucker Proxy), it still has recent blockbuster hits, as well as classic documentaries and more.

Alex Pyryt is a DIY Instructor & Research Specialist at Howard County Library System Elkridge Branch.