By Gabriela P.

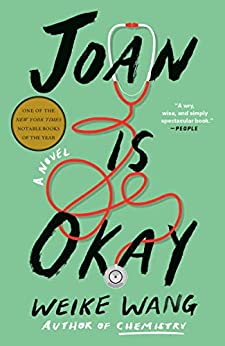

When we meet Joan, the titular heroine of Wang’s novel, the first assessment might be that her story starts where others potentially end. She has everything: she’s in her mid-thirties, living in Manhattan, and a brilliant attending I.C.U. physician. She is ticking off her American Dream checklist, seemingly without a hitch. Having grown up in California with poor immigrant parents, Joan views professional success as a great equalizer. “The joy of having been standardized,” she says, “was that you didn’t need to think beyond a certain area. Like a death handled well, a box had been put around you, and within it you could feel safe.”

But is Joan, or Jiu-an, OK? Of course she says she is. After all, doesn’t she tell her coworkers so everyday, during their brief and polite interactions? Yet they never feel connected with her and would be the first to doubt her response as genuine. While there is concern from some, as when Human Resources reaches out over her excessive shifts, there are also those who delight in her seemingly irreplaceable work ethic. The hospital director calls Joan, “a gunner and a new breed of doctor, brilliant and potent, but with no interests outside work and sleep.” In the first few pages we spend with her, upon receiving news of her father’s death, she flies to Shanghai for the funeral and back in only 48 hours.

Joan’s wealthy older brother, Fang, thinks she needs to give up the Upper West Side for the safety of the suburbs and start a private practice. His wife, Tami, thinks it’s high time Joan gets married and starts a family, because, “a woman isn’t a real woman until she’s had a child.” Her mother fails to connect with her through shopping, and even her neighbor is a habitual overstepper. To everyone in her orbit, Joan is someone who has to be taught how to live.

But as the story progresses, Joan ends up having to reflect on her obsession with productivity as she takes a hard look at her relationships to family and society. “Was it harder to be a woman? Or an immigrant? Or a Chinese person outside of China?,” she asks herself. “And why did being any good at any of the above require you to edit yourself down so you could become someone else?”

The developing Covid pandemic looms over the few months we spend with Joan, which impacts her personally as well as professionally. Wang details the news coming out of Wuhan and elsewhere matter-of-factly — increasing case counts and deaths, border and business closings — sparking a sense of dread in readers who know all too well what’s coming. Joan deadpans: “Some government officials also believed that it was important to keep the American people informed and reminded of where the virus really came from. So, the China virus, the Chinese virus, the kung flu.” Online she starts to see, “clips of Asian people being attacked in the street and on the subways. Being kicked, pushed and spat on for wearing masks and being accused of having brought nothing else into the country except disease.”

Joan is angry. If there is one thing that Wang knows is important for her character, it’s to keep her emotions unmuted to the reader. While cool on the surface, Joan bubbles underneath. Her deeper self only seeps through via dry comebacks that leave others chuckling uneasily.

So Joan probably isn’t OK. She’s a bit awkward, tense, and has complicated relationships with family as well as an affinity for work that others can’t seem to wrap their heads around. But Wang gives us a character so unapologetically true to herself that you can’t help wanting to get to know her, even when it’s pretty clear that she wants nothing more than to be left alone.

Wang’s narrative poses subtle questions about belonging and the definition of “home.” There are moments of unexpected tenderness and reminders of the devastating toll the pandemic had on communities and the individuals within them. And of course, the reader has to ask themselves at the end whether anyone is really OK, and if it’s such a bad thing to be.

Gabriela is a customer service specialist at the Miller Branch. She loves long walks, reading with her dog, and a good cup of coffee.